Teams and teamwork are all the rage. Today, this is how we learn, work, and create in corporations, colleges, and universities. I know this first-hand, from my experience teaching at the University of San Francisco. And this past semester, thanks to my students, I stumbled upon a new way to make any team – say, your team – bigger, smarter, and even more creative.

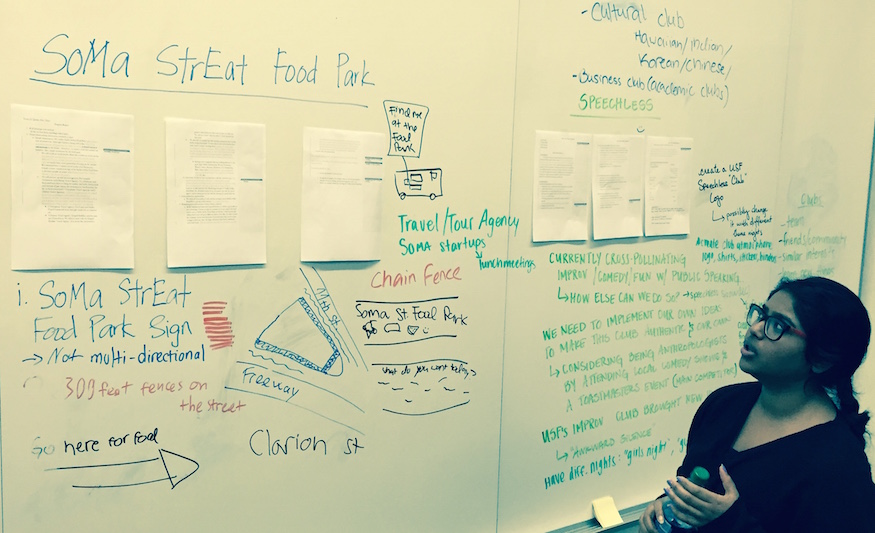

The idea came by accident. Teamwork and immersive experiences have always been a critical element of my classes, and each semester, I have my students divide into teams of three or four tasked to collaborate on multiple projects. We periodically leave the classroom for immersive observations and experiences at San Francisco’s Ferry Building, Soma StrEat Food Park, and numerous exercises on the USF campus, all culminating in a final project working with a real business and mentor.

Last semester, a visiting foreign student suggested that we swap teams for each of our half dozen projects. At first, this struck me as a crazy whim. The challenge and advantage of a team – in college, sport, or work – is the bond you form with your team. In fast order, you must develop chemistry, organization, and collaborative skills. That’s not an easy task, and so I considered dismissing this student’s disruptive idea out of hand. But then, I thought, the name of my course is Creativity, Innovation, and Applied Design. Shouldn’t our teamwork be creative?

Teams thrive when they gel, as anyone knows who has watched an elite basketball or soccer squad execute a series of deft passes. Yet college or corporate teams are different. Sporting rules prevent you from poaching a player from an opposing squad. But borrowing talent or inspiration isn’t forbidden in college or business (think mentors or consultants). Instead, a limiting factor in academics or the corporate world may be how we evaluate people and achievement, or grades and promotions. And there’s another potential obstacle. Our ability to truly see and understand things with fresh eyes is often dulled by our current obsession with all things digital. Technology can push us inward before we’ve travelled far enough afield to find a novel path.

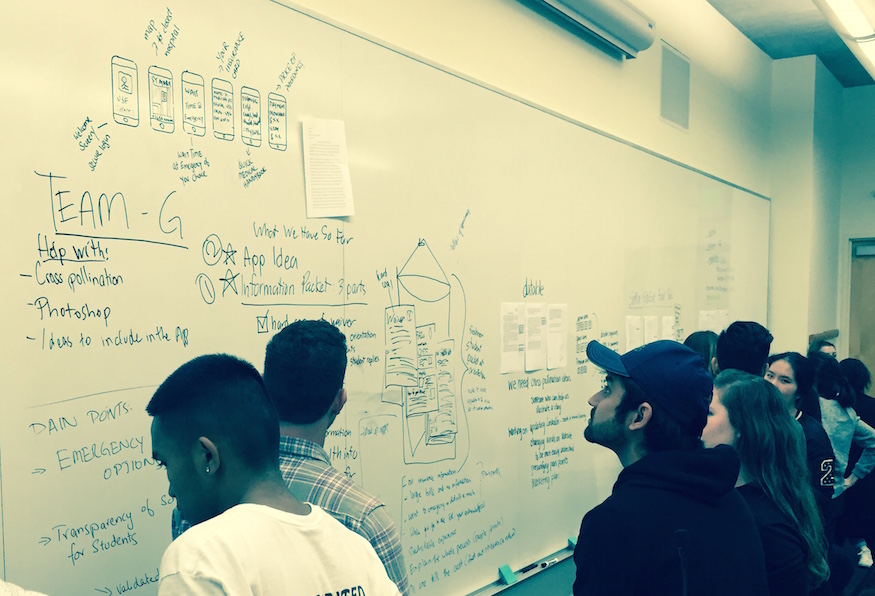

One of the great traditional things about college is that it happens in a formative place where students can find and build on inspiration. My class met in one of the largest classrooms on campus. Behind the podium stood a giant whiteboard, about ten feet high by more than 30 feet long – a great big horizontal canvas waiting to be filled with ideas. I brought a dozen markers in various colors, and packs of multi-colored Post-It notes.

After our third weekly four-hour session, I had each of my seven small teams begin sharing their projects. Topics ranged from innovating the university, to creating physical prototypes for new products, to ideas to improve a real business. On the whiteboard, they would share initial pain points, observations of customers or businesses, and areas of research and interviews. They’d also address the most challenging element, how they might cross to unexpected influences, cultures or companies. This method of breaking through the ordinary to achieve fresh approaches, tactics and ideas is what we call cross-pollination.

Today, we hear a lot about Open Innovation in business, a buzzword that at its heart is about being receptive to new ideas from disparate fields and sources. And yet the term is misleading, because openness is only the beginning. You need glue, what I call Open Teamwork. Up on the giant whiteboard, all seven teams could immediately get a snapshot of all the other teams’ projects. And then we did something different. We temporarily rotated talent: two members of each team joined the team to their left, and were tasked with evaluating another team’s board, writing up suggestions and ideas on the board or on Post-It notes. Fresh eyes can bring a fresh perspective, come up with new ideas or observations, discover what appears to be missing, or give a gentle push to help stuck teams explore crossing ideas from other fields.

The Team Swap worked like magic. Students who had never talked or shared ideas were now actively providing constructive feedback, thinking about their own work in different ways, and pushing every team to improve its process. Next, I asked teams to make projects as visual as possible with sketches. Not everyone could draw, so I assigned one talented student to assist the teams who needed help with visual representations of their ideas. The visual element freed projects from the often linear constraint of words, and made it easier to see and mold a business experience.

The whiteboard became our foundation, and we naturally began allocating more time to this collaborative process. Students would regularly share the project insights they gleaned from their out of class experiences. They’d even share team papers – taping them up on the board. Sharing in this collaborative space allowed the class to learn from seven projects at a time. The class went from mono to stereo. You were on a team, but you were also part of a class, and students took pride in helping their classmates.

The quality of work improved. Not every student excelled (one team was below average despite my best efforts), but three teams became extraordinary, achieving some of the highest quality work I’d ever seen. Several students shared with me that they’d never experienced such a high level of camaraderie and trust. They loved their teams.

Prototyping is at the heart of learning and teaching. My next plan is to put these same techniques to work for creative corporate ideation sessions and innovation labs. Class at USF starts up again soon, and I’m eager to test out a few new ideas, beginning with inviting a couple of last semester’s star students to share their projects and insights in miniature, ten-minute lectures, featuring their best work. I’m pretty sure my new students will come up with great ideas too.

The whiteboard awaits.