The spillover crowd at Reinvent’s What’s Now San Francisco event at Capgemini’s Applied Innovation Exchange was hungry. The French IT firm was pouring plenty of good wine as usual, but attendees were crowded around Hooray, a startup with a pan sizzling with bacon that looked and tasted like the real thing. Except that not a single piggy had been harmed in the process. Just like the many heaping trays of appetizers being devoured nearby, this bacon was completely plant-based.

Peter Leyden, CEO of Reinvent – a popular, long running series of topical deep-dive conservations in SF and NY – welcomed the 150 attendees to the evening soirée with some context. “One of the spaces we really haven’t done as much on is what I would call biological engineering, synthetic biology or biotech,” he said. “And so we’ve got a treat tonight because this is really the least understood of the technology revolutions, food tech.” And with that, Leyden introduced his engaging guest speaker, Dr. Liz Specht, Associate Director of Science and Technology at the Good Food Institute.

Specht began with the central dilemma that drives the institute’s mission: “How do we feed ten billion by the year 2050 in a way that won’t completely ransack the planet, that’s not flagrantly wasteful of resources, and that doesn’t compromise global or public health?” She rattled off the megatrends: precision agriculture, indoor and vertical farming, moving food production closer to urban centers. Then quickly jumped to her true love, “alternative proteins” with a provocative statement:

“In the year 2050, we won’t need animals anymore, but we will still eat meat.”

It’s a fascinating theory, and Specht set out to support it with facts and trends. There’s ample evidence that our current obsession with eating animal meat is not sustainable. Producing meat is one of the largest contributors to global warming, and the world is running out of resources. Fifty percent of the world’s habitable land is already used for food production, said Specht, but a stunning three quarters of it is already pasture or range land dedicated to livestock production. Growing meat the old fashioned way, not surprisingly, is woefully inefficient. Chicken offers one of the best returns on your energy investment. Put nine calories into a chicken and you get one out. Cows are especially uneconomical – a 25:1 feed-to-meat conversion ratio. Then there’s the terrible environmental damage: livestock spew nearly 15 percent of all greenhouse gases worldwide and cows are by far the worst offenders.

The trouble is that humans continue to go bananas for the protein and taste of meat. Demand for meat is skyrocketing worldwide. But Specht argues that in just the last few years our framing of the problem has begun to offer an alternative, potentially less environmentally destructive path. “It’s no longer, how do we get to eat less meat? It’s how do we make meat in a better way? How do we make something people want?”

Specht answered her own question by smartly letting the data and graphs do a lot of the talking. Alternative meats are hot. She clicked through dramatic slides showing sudden near-vertical “hockey stick” graphs, representing the sky-rocketing growth in fast-food chains and retailers offering the latest alternative meats. Stunning developments like Burger King offering the Impossible Burger in over 7,000 locations. Tim Horton testing Beyond Sausage patties in over 4,000 locations. Traditional meat purveyors like Morningstar Farms, Hormel, Smithfield and Tyson jumping into the meat mimicking business.

Why the explosive growth? The food industry appears to have zeroed in on what marketers call perfect market fit and nailed what attracts traditional carnivores, “To make products like Beyond Sausage or the Impossible Burger that look and taste and smell and have the same nutritional punch as meat,” said Specht “and serve as that one-to-one drop-in replacement.”

Incredibly, this may be just the current future of food. The next wave: “Getting that structuring right,” said Specht who has a PhD in biochemistry, “getting those plant proteins to really align in fibers that feel like muscle fibers and muscle tissue.” Producers will soon perfect not only the texture but also the “right kind of juiciness of the bite, and the right fat content.”

Not far off, predicted Specht is lab-grown meat. In combinations we can only imagine. She pointed to Geltor, a company specializing in collagen, that has already made high protein gelatin candies from the DNA of a woolly mammoth. “In generation 2.0 can we get much more creative about this?” said Specht, provoking the audience. “Can we think about creating combinations that never would have been possible? Your marbled steak with Omega-3 fatty acids?”

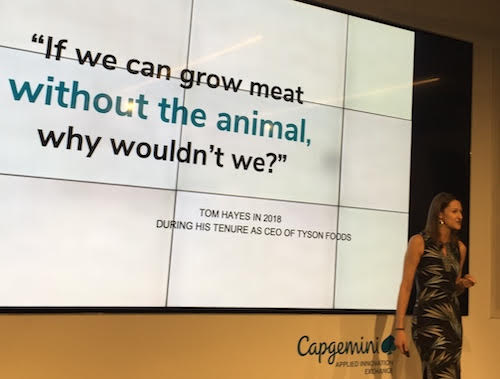

Where oh where is all this futuristic biotech taking us? To a kinder, gentler future where we spare the animals and the planet? Specht ended her talk with one of her favorite quotes. Not from a seer passionate about climate change. Or a famous utopian. But by Tom Hayes, the former CEO of Tyson Foods, the world’s second largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef, and pork.

“In the year 2050, we won’t need animals anymore, but we will still eat meat.”

Indeed.