Consider this dicey scenario: what to do when your co-founder goes rogue and fabricates a story about a prior investment to dupe new funders? Or this one, ripped from last week’s headlines: how to respond if you’re a scooter-sharing startup founder and a glitch in your software results in a spate of injuries as riders are pitched off their rides into traffic? It’s not always easy to determine the right path – ethical, evil, or somewhere in between. But this week in San Francisco, we dove into these and other thorny dilemmas, at our “Ethical Innovation (or Not)?” workshop at Schoolab.

We lead labs all the time on innovation and entrepreneurship, here in our home city and abroad. Our main stock in trade is putting groups in fun, immersive environments, to cross-pollinate concepts for new product ideas. On Monday, thanks to Mathieu Aguesse, CEO of San Francisco’s brand-new Schoolab incubator and his co-founder Ana Maria Zuluaga, we explored a provocative angle on social innovation with 30 bright students from the Paris-based ESSEC’s Masters in Entrepreneurship program.

Ethics aren’t easily taught in the abstract. A principled value system only truly emerges in context, through actions or, more commonly, reactions. You can think of this code of conduct as a kind of back-of-mind lens through which decisions are filtered. So we devised scenarios to address the technical, financial, and social aspects of running a company, and dove in together to brainstorm with creative solutions. This was a prototype lab, a trial run, and we were blown away by the level of engagement from this European group. Their willingness to tackle messy situations with no easy answer. Their ability to mitigate, pivot, or respond with a unique perspective. The students designed fascinating strategic outcomes that were not always about making the most money or attracting the largest user base.

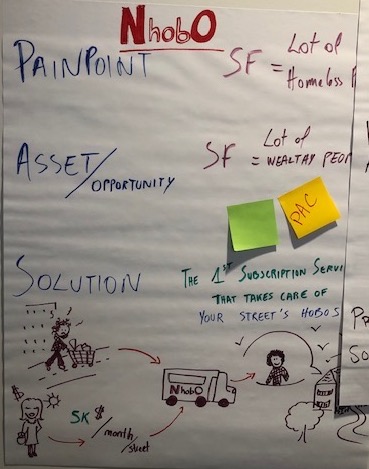

In an age when so much of tech is focused on funding and outsized exits, there’s something grounding about building a principled mission into your startup. Adding ethical considerations to your decision-making process may improve your ability to course-correct when the road gets slippery. Indeed. By the end of our workshop, several of the student teams brainstormed playful, original ideas for companies that set out to take an ethical stance from the get-go. Our favorite idea, one we’d love to see come to life, was “Nhobo”, a service that would address the homelessness crisis in San Francisco by tapping a local, deep-pocketed customer base to subscribe to an adopt-a-street program to improve the lives of homeless denizens while keeping the area safe.

Schoolab is a welcome new arrival to SF’s bustling tech ecosystem, a valuable resource for foreign and local students alike. Headquartered in Paris, Schoolab has diverse offerings in innovation, entrepreneurship and startup acceleration. The Schoolab model brings the idealism and fresh eyes of young student consultants to corporate challenges, encouraging collaboration and co-creation. We see a fresh opportunity. With topics like ethical innovation on the roster, Schoolab students may help corporate clients navigate ethical disasters before they lead to scandals or costly damage control. Top French mentors are one of their best assets. As we wrapped up the workshop, the students regrouped for an animated insider talk from Jean-Louis Gassée, tech industry dignitary, once Apple’s head of Macintosh development, and now a prominent VC. He shared his secrets of pitching and getting early investors (“tell them you’ve got just three slides”), before taking questions from the aspiring founders.

Theory in Action

The night after our workshop, the head of a drone mapping platform that serves the engineering and construction industries disclosed yet another ethical dilemma. The software is open source, so anyone can use the technology, and it’s been applied predominantly for good purposes. He described thousands of use cases in search-and-rescue missions, medical deliveries, preventative assessments, and plenty of straight-up successes. But he also knows militant jihadists have used the platform to carry out nefarious reconnaissance and deadly drone strikes. He’s contemplative, if not conflicted. What might he have done differently as a creator of the technology? What could he do now? What are his own ethical responsibilities? You tell us.

We’ll be building this is a real-life scenario into our next lab.