Mathieu Guerville collects failure. Not just any failure. Catastrophes on the scale of Enron, Bernie Madoff, and Lehman Brothers. In a career in which he is charged with picking winners, surrounding himself with objects of failure may be how Guerville increases his odds of success.

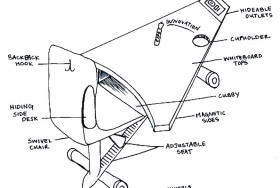

Born in France, Guerville studied marketing there, and then later economics at Northwestern in Chicago. His curiosity about business and scandals began early. As a ten-year-old, he’d stay up late Sunday night to watch Capital, a TV show about business that occasionally touched on scandals. He eventually went into business in Chicago, and rose to become a Director of Strategy and Business Development for Underwriters Laboratories (UL). His childhood fascination had become his career. So, when an acquaintance happened upon an authentic, “confidential” inter-office manila envelope from the bankrupt Enron, Guerville snapped it up for $50, and in the process became aware of a whole world of similar treasures available on eBay. He binged on artifacts of catastrophe. He bought a can of the failed New Coke (still full), the Bernie Madoff Jewelry Liquidation Catalogue, and a Lehman Brothers Emergency Evacuation Kit, oddly consisting of “a whistle, blanket, matches,” and other arcane useless items that in the end couldn’t save employees from the firm’s tragic demise.

Guerville expanded his reach to “systemic crashes.” He began collecting relics from dotcom dinosaurs, including the sock puppet from Pets.com, and the Employee Welcome Kit from Webvan. He sought to underline the naivety and vulnerability of investors, through newspaper articles predicting the stock market’s rebound at the outset of the Great Crash of 1929, and a magazine article presenting Charles Ponzi as a phenomenal investor, before the name became synonymous with fraud. Guerville bought two to three items a month over the first four years of his obsession. He set up software on eBay to execute last-second automated bids in order to snap up his most coveted items. As his collection expanded, he saw it had a greater purpose. Business people and entrepreneurs study success far more than failure. But as Guerville’s responsibility in his job grew, he began vetting companies for a living. His collection embodied a visceral and intellectual reminder to be vigilant in finding the potential weakness or fraud in a company. “I buy companies for a living,” he says. “So by putting myself in the shoes of somebody trying to buy Enron stock or invest in Bernie Madoff’s fund, it reminds me that a lot of people way smarter than I am got conned.”

Today, working in San Francisco, Guerville says his favorite piece may be a centuries-old calligraphic depiction of one of the first major international economic crises, the South Sea Bubble of the early 18th century – fascinating in no small part because today Guerville expects our own tech bubble to pop. Collecting failure is more than a hobby. “I’ve seen a lot of bad stuff thanks to my collection,” he says. “This helps me think more about what could go wrong with a business. It’s the law of big numbers. One of these companies is likely to be doing something horrible, probably in a way that hasn’t been done before.”

Guerville calls these artifacts of doom his “cynical angels.” A reminder that if something seems too good to be true, it probably is.