Entrepreneurs and startups face the challenge sooner or later, what are we going to call it? The web is full of amateur advice, not to mention plenty of lousy names for products, apps or companies. The path to a cool one is rarely obvious. But here’s my suggestion: study the man who cut his teeth managing a Seattle comedy club, learned to soak up ideas by hanging out with some of the legends in comedy, and then tapped that eclectic background as a core creative member on the team behind such powerhouse brands as the Pentium and PowerBook, and named Coca-Cola’s Dasani water and the BlackBerry.

Marc Hershon’s great love was comedy and improv, and strangely enough, that quirky terrain prepared him for a career in naming and branding. After stints in radio, Marc got a job as manager of the floundering Comedy Underground in Seattle. He “treated the comics really nicely,” took reviewers out for lunch, and within six months, Jerry Seinfeld, Paul Reiser, and Dana Carvey were headliners and the Underground had become a hit. “I’d meet them at the airport and take them around town,” said Marc. Dana Carvey loved going to the movies, Will Durst preferred the Pike Place market. Seinfeld “was a really nice guy. He just wanted to hang out, maybe get lunch.” Marc began to see how Seinfeld and other comics turned mundane daily foibles into the grist of comedy. “They had these observational techniques. We would be doing something during the day, and I’d begin to see how some of those observations would later appear in their routines.” Tellingly, Marc would later find that these shrewd observational techniques played a key role not only in comedy but also in naming.

Seinfeld told Marc that he roughed out his jokes in a holographic style. “He takes a topic and looks at it from every conceivable angle. Say it’s his famous bit about putting socks in the dryer. He looks at it from the perspective of the person who put the socks in, then from that of the dryer, and then from the point of view of the socks. Then, he thinks about those observations. He lops off ones that don’t work. Then he works and reworks the language. Great comedians find the funny way to say something. It’s like the ancient way of saying a magic spell. It’s about finding the right word.”

Finding the right word became Marc’s passion. He worked closely with Dana Carvey on jokes and scripts, and performed and taught improv, often with Sammy Wegent of Speechless. Marc got the rare opportunity to see how each performer approached his craft. Carvey “is telling more of a story,” said Marc. “He’s doing dialogue, and he’ll throw things in. He’s constantly experimenting.” To prepare for an appearance on The Tonight Show, for instance, Carvey maps out bits on big yellow legal pads and experiments on local Bay Area audiences. “He’s got circles and lines and arrows drawn from one to the other. It’s split up by topics. He carries it with him to gigs and takes it out on stage. It’s the way his brain works. He can access that paper because of the symbols.”

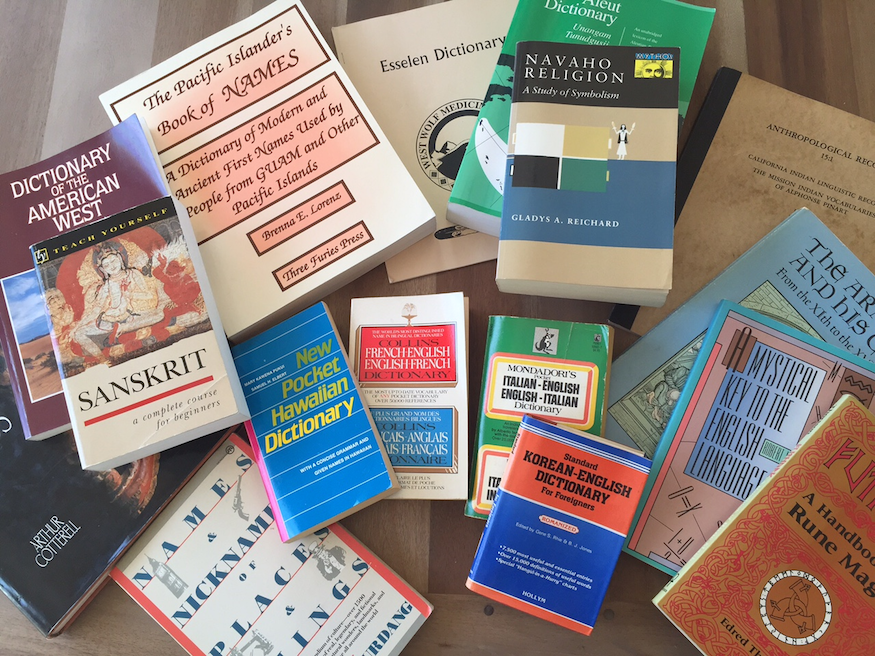

Marc’s work with Carvey, and years of doing improv, including with Robin Williams, helped him untangle how these extraordinarily creative men took unpredictable paths to get laughs. It was that freedom from routine that ultimately led Marc to name products at Lexicon Branding with a style rooted in rejecting the traditional. Founded and led by David Placek, Lexicon Branding in Sausalito, CA., has earned national press for some of the brand names it dreamed up for Apple, Microsoft, Intel, Hewlett Packard, and P&G. Placek is a pioneer of gauging how certain sounds influence our connection to names, and a proponent of what his firm dubs a “comprehensive” team approach that includes computer generated lists, brainstorm sessions, creative sessions, proprietary databases, libraries, and software. Marc worked closely for eighteen years with Placek and a few others at the firm on several hundred naming projects.

Travel for Marc became a time to be “on the lookout for odd resources — reference materials, books maps, pamphlets.” Years ago, when performing improv in Four Corners, New Mexico, he chanced upon a gigantic Navajo/English dictionary for sale in a video store. When Coca-Cola wanted a “new to the world” moniker for a mineral water targeted toward young women, Marc pulled out the Navajo tome and found a word that roughly translated into “the power of the grandmothers” By slicing and dicing, he fashioned the name Dasani out of an idea dating back thousands of years.

Marc coined his most famous product name in seconds, by conjuring an iconic visual image. “This dinky company from Waterloo, Ontario had created this device to read the email on your computer while away from your desk,” said Marc. “They had some prototypes and a placeholder name. PocketLink, that was the name we had to beat.”

It looked to Marc like an old-style pager. Black plastic, two-line display. Marc held it in his meaty palm during the first meeting and offhandedly said, “It kind of looks like a high-tech blackberry.”

To Marc, it was just a casual observation, but the Canadian marketing director practically leapt out of his chair: “Oh that’s really cool!”

“What’s cool about it?” asked Marc.

“Because there’s no such thing as a black berry.”

The Canadians weren’t familiar with the fruit — they call a similar berry the loganberry — and that ignorance may have been a blessing, because it heightened the novelty and kept the company from settling for a more ordinary tech name. BlackBerry was a breakthrough name for a breakthrough product. Sales exploded, and for many years the BlackBerry was the world’s dominant cell phone, all because a guy who loved comedy realized that observing the mundane can often reveal something extraordinary.