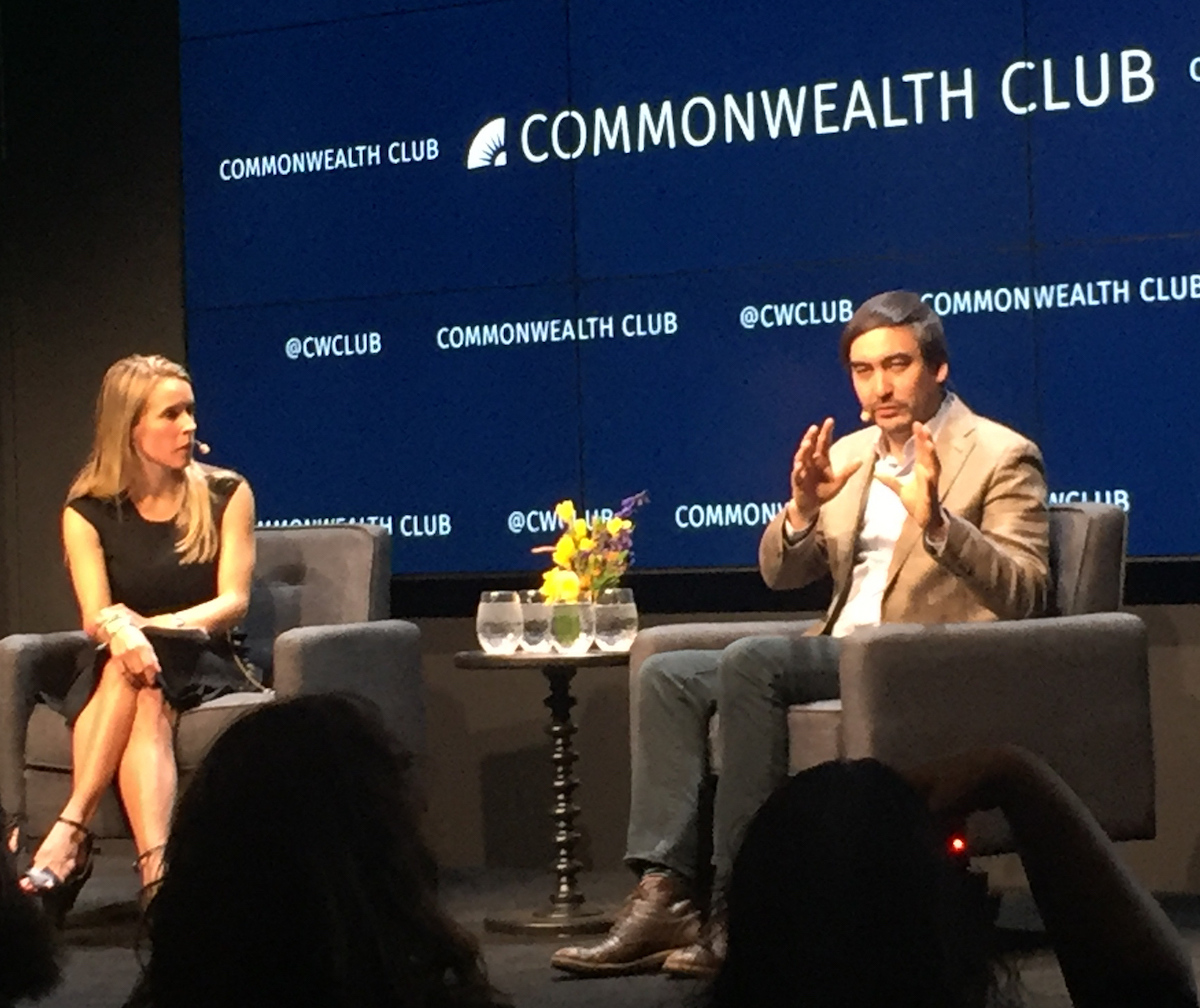

Facebook and other tech giants have been “getting away with murder on privacy” and other abuses of the public trust, declared Tim Wu, Professor at Columbia Law School and author of the new book The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age, at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco last week. A day of reckoning may finally be coming, he told the packed crowd. An essential reboot of this new Gilded Age of Silicon Sultans and the monopolies they oversee.

Wu spoke in conversation with Alexandra Suich Bass, The Economist’s Senior Correspondent for Politics, Technology and Society. Wu knows the law, the regulators and the tech firms. He’s clerked for Justice Steven Breyer, and worked at the White House National Economic Council, Federal Trade Commission and in Silicon Valley’s tech telecommunications industry.

The Curse of Bigness is a call to action for a revival of basic consumer protections gained through enforcing long-ignored antitrust laws. “We have at some level given up on the primary goals of the antitrust laws, which were once to ensure that the economy was competitive,” said Wu. History informs us that wasn’t always so. Keeping prices down and sustaining healthy competition were paramount when Theodore Roosevelt took on J.P. Morgan, John Rockefeller and other industrial robber barons at the turn of the 20th century – bold legal and political actions that he believed were necessary to prevent an otherwise inevitable revolution. The “Trust Buster” broke up monopolies in a series of industries, and antitrust and anti-monopoly laws were strongly enforced by federal and state regulators up until about the 1960s, said Wu, when the pendulum began to swing in the other direction.

Blame it on the lobbyists: the more powerful an industry, the greater the prowess of its lobbyists, and the more organized their efforts to influence Congress. Today, he said, we are living with monopolies in multiple industries – from airlines to telecommunication firms to pharmaceutical conglomerates. But the biggest threat to consumers may be the tech giants, said Wu. Without competition or regulation they do what they want. Play by their own rules. Facebook “bludgeoned [would-be competitor] Snapchat with Instagram and WhatsApp,” Wu said. Google all but killed off Vimeo with its acquisition of YouTube. These are what Wu called cases of “a platform eating its ecosystem.” One reason these giants have been able to skirt antitrust laws is that in many cases the companies they’re absorbing are not making money, and this business model stymies regulators. “I think the key problem is [the regulators] didn’t understand the metrics by which the industry was operating,” said Wu. “They were looking for cash. But these firms were competing for… audiences.”

Who’s in Charge?

Facebook, he argued, lacking competitive pressure, may have hurt American consumers the most. They failed to protect users’ privacy and were willing to “run enormous security risks” that led to the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The bill is finally coming due: The Federal Trade Commission, Wu’s former agency, is expected to push for a multi-billion dollar fine in the coming days, one of the largest fines ever against a tech firm.

Competition provides healthy market advantages, Wu explained, citing the birth of the global software industry from the breakup of IBM’s lock on the conjoined hardware and software market in the 1970s. He contrasted our economy and political history with that of Japan, where an absence of government interference in tech monopolies such as NTT and NEC effectively quashed the potential for independent software development or startup culture. American history may repeat itself. Our 2020 presidential election, Wu thinks, may bring these competitive issues front and center, echoing the 1912 campaigns by Wilson, Roosevelt and Taft, whose platforms explicitly addressed market levers to keep monopolies in check.

But perhaps Wu’s biggest argument for antitrust control is the suggestion that we could stem disturbing recent trends in economic disparity. As tech goliaths continue to rake in revenue unchecked by regulators, he said, with huge tax breaks or even tax waivers, “higher profits go back to shareholders, the management or narrow class of professionals, and not extended to employees.” The top 1 percent in the US earn almost a quarter of the national income and control a disproportionate share of the national wealth.

Without the check of antitrust, this tremendous new wealth and political decision-making power has been ceded to a handful of tech companies and their shareholders. Wu suggested we should be asking who’s really in control. And, are they doing more harm than good?

Such is the Curse of Bigness.