Here’s why you don’t want the FBI snooping on your iPhone, or anyone else’s. It would be very bad for innovation. “Ideas are so fragile,” Craig Tanimoto, the man who dreamed up the revolutionary “Think Different” Apple campaign, told me recently. “If they’re not ready, and if you’re not ready to defend an idea, it can be killed instantly.”

Entrepreneurs and innovators are by definition rule breakers. Rebels and iconoclasts, they are full of contradictions and rough edges. Steve Jobs sold “blue box” phone phreaking devices to help criminals cheat the phone company out of long distance charges, and if the government had known about that crime, there might be no iPhone today.

Look at Uber and Airbnb here in San Francisco – both controversial for disrupting traditional industries, both breaking rules if not laws. Or Twitter, which became a transformative medium of rebellion in the Arab Spring. Do we Americans want to give our government access to countless ideas that, as Tanimoto said, are “not ready” and that may be “killed” before they are even born?

Patrick Hanlon, a friend and consultant who helps people and companies come up with breakthrough ideas, lives by the following maxim: “Don’t put yourself in the hands of people who only know how to say No.”

The FBI only knows how to say “No!”

I don’t trust the FBI with my next idea, and you shouldn’t either. Freedom is a big reason why Americans (especially Californians) come up with so many wild and amazing innovations today. And part of that freedom comes from our culture of openness and a lack of government surveillance.

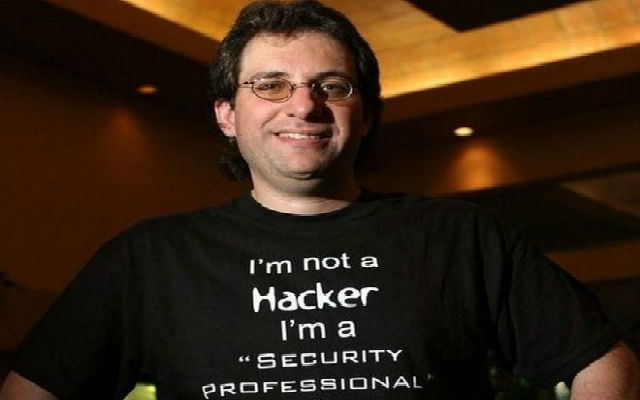

Trusting our government to stay out of our affairs is risky business, and as history shows (such as in the aftermath of Edward Snowden’s extraordinary NSA surveillance disclosures), the government craves backdoor access to our thoughts and possible actions. Back in the early 1990s, American media and prosecutors were obsessed with computer hackers, much as today they are obsessed with terrorists. The media and government launched furious hyperbole around this issue, and hackers were painted by both establishments as dangerous computer terrorists. In hindsight, we know now that many of these “hackers” were pushing the envelope of computing, and leading to positive technology breakthroughs. Indeed, many of these former criminals are now gainfully employed as computer security “white hat” experts.

I happen to know something about this because at the time I was writing about hackers and interviewing dozens of them, sometimes when they were on the run from the FBI. Strangely enough, my writing about criminals led me to be hired to collaborate with IDEO on two books on Innovation. Crime does pay, and ironically, while researching and writing about hackers, I learned a valuable lesson: the FBI and federal prosecutors break the rules too.

Kevin Mitnick, a gifted and notorious hacker, began spying on my email at The WELL, one of the earliest virtual communities and a hub for industry insiders and journalists covering nascent internet and web technologies in the 90s. Next, an amateur cybersleuth began spying on my WELL email and the accounts of a few of my colleagues, and shared his findings with a celebrated journalist and a federal prosecutor on the hunt for Mitnick. This brazen and illicit activity ended up making the cybersleuth, the journalist, and the prosecutor very rich. A huge book and movie deal for the journalist and the cybersleuth ensued, as did a cushy tech job for the prosecutor, now one of America’s highest paid general counsels at a prominent tech firm.

Don’t trust the FBI. They’re hackers too.

UPDATE: On March 3, 2016, Wired reported in an article titled Tech Giants Agree: The FBI’s Case Against Apple is a Joke, “in a wide ranging show of solidarity, dozens of Apple’s tech industry competitors and contemporaries” filed amicus briefs in support of the company’s stand against the FBI. Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, Yahoo et al, warned that the FBI demand is dangerous and unreasonable: “Americans live their lives on their phones…cell phones are the way we organize and remember the things that are important to us; they are, in a very real way, an extension of our memories.”