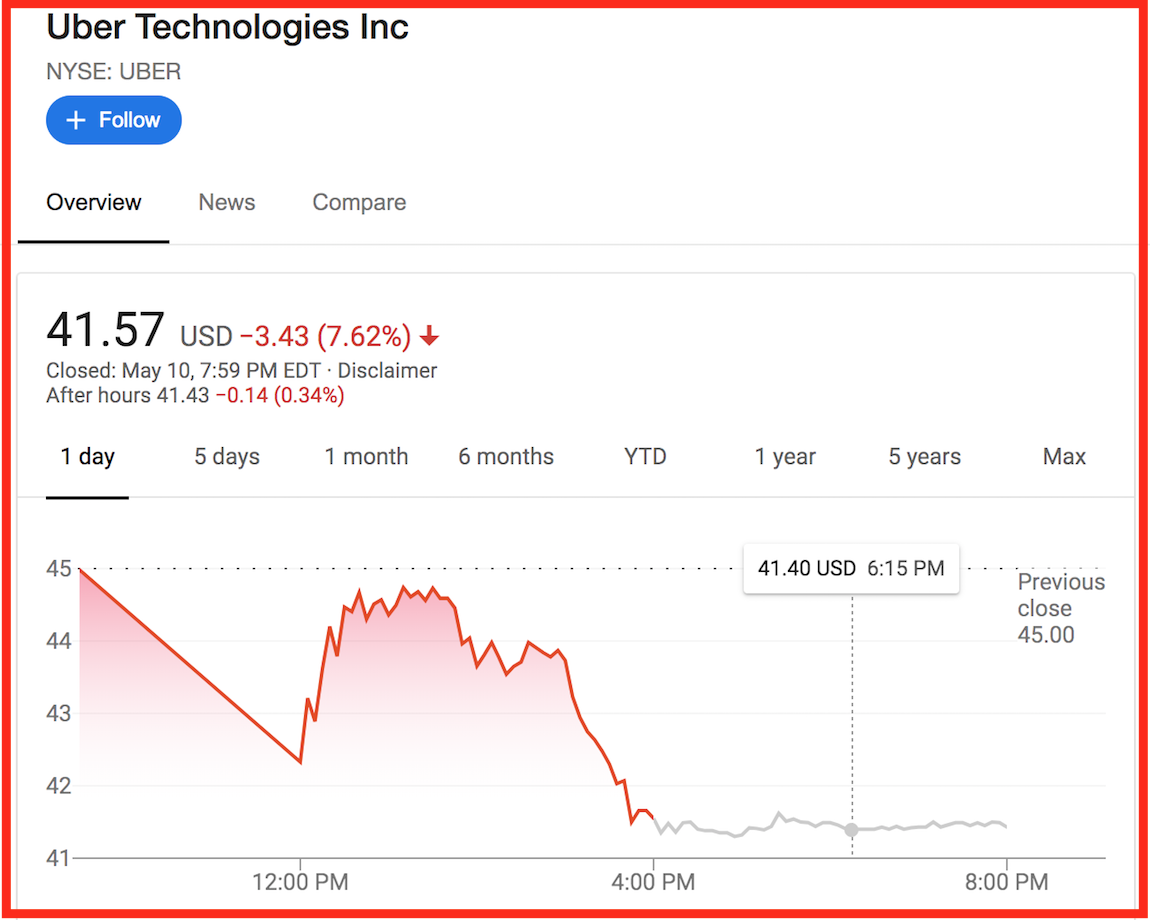

This was meant to be Uber’s week in the sun, the long-awaited mega IPO for the reigning king of the sharing economy. But then came the strike. Tens of thousands of grossly underpaid drivers, many of whom earn less than minimum wage, parked their rides. Meanwhile, the well-timed release of a comprehensive, definitive study revealed that Uber and Lyft rideshare vehicles comprise two thirds of San Francisco’s increasingly horrendous traffic. Predictably, Uber’s IPO hit the skids, becoming one of the worst public offerings in history. What can we learn from this pile-up?

1. There’s a conflict raging between for-profit goals and public needs.

It’s long past the hour for the world’s greatest cities to regain their regulatory authority and push back against the chaos ridesharing has wrought. Cities, transportation agencies, and public utilities around the world were conned by the false promise of tech and efficiency.Uber and Lyft both came out swinging, with a bold promise to dramatically reduce traffic and mitigate pollution. Instead, they’ve clogged our metropoles with more cars, more traffic, and ominously, more air pollution. In San Francisco, for example, drivers are incentivized to commute 50 to 100 miles or more to get to the city, and because no cap exists on the number of cars, many circle around the streets spouting exhaust as they hunt for fares. Earlier national studies have put this traffic and environmental damage at 5.7 billion extra miles driven annually in the US.

This week, a University of Kentucky researcher and the San Francisco Transit Authority published a remarkable study demonstrating that two thirds of SF’s traffic increase in the past nine years has come from ridesharing vehicles. The researchers collaborated with data scientists at Northwestern University to “ping” the Uber and Lyft APIs to get the data they needed to make their calculations. It’s not hard to see how this pattern has been borne out in cities around the globe. Strangely, California cities lack the authority to regulate ridesharing firms, a power held by the Public Utilities Commission, which has done virtually nothing to thwart the problem. Cities can, however, tax the firms, and ballot measures may soon propose per-ride fees. Here in California, with a new pro-environment Governor, evoking climate protection as a rationale could go a long way toward calling public attention to this issue.

2. Silicon Valley’s pitch-big-and-go-IPO model betrayed us.

Uber, Lyft, GoBike, Jump, the scooter entries Lime and Bird and many other much-hyped sharing economy mobility ventures rose to prominence in large part because they fit the Silicon Valley narrative of disruption and potential for global scale. But replacing taxis with ordinary cars was always inherently problematic on simple economic and community metrics. The financials of ridesharing never computed. In the aggregate, it’s hard to see who profits. Drivers earn less per hour than fast food workers, and Uber still lost a stunning $1.8 billion last year. Municipal budgets suffer too, as the ridesharing market has been proven to undercut public transportation ridership and funding. Yet none of this matters to the venture capital firms which have made fortunes by propping up the sharing economy myth for private gain. Investors’ fixation on the Hollywood-style tech pitch helped launch these ventures into the stratosphere. It all sounds fabulous in an elevator speech, where the numbers don’t have to add up. But let loose in the marketplace, it’s only the bankers and inside shareholders who cash in on the fiction.

3. The crowd is complicit.

It’s not enough to blame venture capitalists, Uber, Lyft, negligent state regulators and transportation bureaucrats. We, you, and millions of customers like us, deserve our share of the blame. It’s long been clear that ridesharing companies are messing with our cities, diminishing our quality of life, and popularizing an unsustainable gig economy that threatens to create a generation of have-nots. Yet we still pull up the apps, and ride. The illusion is starting to wear thin, the characters once hailed as saviors now coming into focus as brazen profiteers. Even with bad boy founder Travis Kalanick in the rear view mirror, the Uber drivers’ strike makes it clear there’s a large sector of the population who are harmed by the choices we make out of selfish convenience. This week, the New York Times summed up Uber’s quandary: “There’s a good reason for the company’s lackluster initial public offering: There is no future for Uber as we know it, and no one knows if the company will ever make the leap to a profitable business model.” It’s far more than just Uber’s problem. Cities and citizens need to wise up to the broken Silicon Valley IPO culture that helped create this monster. Let’s hope we don’t buy the charade of disruption so easily next time around.