Forget for a moment technology. One of the planet’s most heavily financed startups is waging an all-out assault on where and how humans come together to create this digital domination. Welcome to WeWork, a sleek, tech-infused real estate movement profiting from the booming global trend in mobile anywhere, anytime work.

WeWork founders Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey have attracted nearly $5 billion in capital to value their firm at roughly $20 billion, exceeding the investment raised by Airbnb. The numbers are staggering: 130 locations in 30 cities, with 100,000 members working across 7 million square feet. This is the Starbucks of co-working spaces. In New York alone, WeWork sports an astounding 38 locations, from Soho to Midtown, Brooklyn and Harlem, as well as a WeLive on Wall Street, an upscale experiment in branded all-in-one communal living.

San Francisco – a pioneer in the co-working and tech incubator revolution – is home to no less than seven WeWorks with 9,000 members (an eighth space is opening this summer). Each hosts teams from Fortune 500s, small businesses and entrepreneurs, with about 50 percent of the members loosely classified as startups, far higher than the national WeWork average of 20 percent. Tenants are drawn to the appeal of the ready-made, off-the-shelf office over the challenges of the DIY alternative.

An International Co-Working Arms Race

WeWork has so much cash it can’t seem to give it away fast enough. The firm just announced its $20 million “Creator Awards” program, handing out the first $1.5 million to 25 entrepreneurs in Washington DC, with events in Detroit, Austin and London scheduled this spring and summer and more in the fall. The headlong rush to open co-working spaces and tech incubators – brimming with all manner of incentive packages, from no-commitment, month-to-month rent, free classes and workshops, access to industry mentors, bike storage, private phone booths, business services, fresh fruit water, ping pong, ample happy hours and more – is nothing short of an international arms race, one I’ve had the chance to see firsthand. I recently hosted Mao Daqing, the co-founder of Chinese co-working company UrWork (sometimes referred to as Asia’s WeWork) in San Francisco. We toured Galvanize, the all-in-one tech campus, incubator, and corporate innovation lab, and the equally impressive swissnex foreign tech hub on Pier 17. Mao was in town to conduct market research to inform the growth of his own well-financed firm (valued at $1 billion USD), which is rapidly expanding and exploring new models throughout China. To give some sense of the surge, in Shanghai and Beijing alone, there are thought to be well over 500 incubators and co-working spaces, a dramatic increase from the handful that existed in 2015.

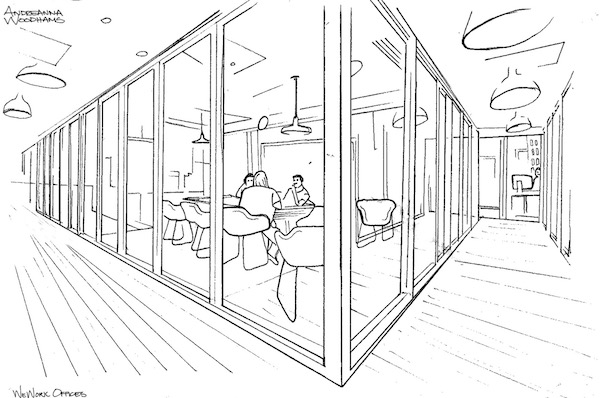

WeWork boasts a first-to-market edge both in the US and internationally. The company’s strategy is to meld the hip, millennial vibe of a fashionable incubator in revamped office spaces, with the goal of attracting a broader clientele of traditional companies and increasingly mobile workers. WeWork offices show well, offering a branded, clean, polished look – featuring hardware floors, pendant lighting, trendy industrial design, as well as startup-style perks like ping pong and foosball tables, comfy couches and lounges, and all the free beer and Kombucha on tap you could ever drink. These details matter. The professional quality and operations of independent incubators or co-working spaces can be uneven. The polish of WeWork appeals not only to the shirt-and-tie establishment, but also to larger new tech firms in search of alternate work hubs to spark collaboration and partnerships. In San Francisco, for instance, corporations are leasing whole floors at WeWork locations, and Fortune 500s tap them for satellite offices (often dubbed “micro-offices”). Amazon has taken a whole floor at the new Embarcadero WeWork building. WeWork’s aggressive growth and dominance raises an interesting question: will it remain cool to work at the New Mainstream?

The advantages are many. Individuals, startups, small businesses, or corporate staff can join and start working almost instantly at a WeWork. Membership grants access to conference rooms worldwide, ideal for traveling executives and salespeople. The company touts the benefits of standardization, the familiarity and comfort in knowing how a conference room looks and works (furniture, AV, fixtures, etc). Abundant basic business resources are also included – from WiFi, to Ethernet, to printing, file storage, and even discounts for healthcare, payroll and Amazon Web Services, as well as events and classes.

Why is WeWork so highly valued by investors? The firm’s snug, often glass-walled offices– priced at about $1,800 a month for a two-person office at the prime San Francisco Transbay location, and $450 for a hot community-style desk – amount to a profitable markup. Tenants are essentially paying a little more for what’s marketed as a superior experience and buzz. WeWork’s compression model – more people per square feet – is offset by the quality of the design, ambience, services, free events, and membership in a growing international WeWork tribe.

WeNext: A Gold Mine of Data on How We Work and Live

Expect WeWork to scale and expand into related businesses, including its nascent WeLive concept, a mobile workers’ twist on senior living. The New York location features studios starting at slightly over $3,000 a month, and bedrooms in shared spaces under $2,000. The company advertises a “new way of living” built upon community and flexibility: “From mailrooms and laundry rooms that double as bars and event spaces to communal kitchens, roof decks, and hot tubs … WeLive fosters meaningful relationships.”

Co-founder Neumann is not short on ambition, once joking that his ultimate vision was “WeWork Mars.” While skeptics argue the firm may be overvalued, and that office realty giants might one day squeeze out the upstart, the WeWork model already feels like a well-oiled machine, along the lines of Starbucks. And while not everybody loves Starbucks (or its coffee) and WeWork may not be the right fit for some startups and entrepreneurs, (not everyone cottons to the compression) that standardization has the potential to scale, especially as the corporate world finds its more talented workers hungry to leave the confines of their outdated campuses.

WeWork increasingly highlights the power of the crowd and its self-driving momentum, suggesting that its 100,000 WeWork members may profit through joining an international network of entrepreneurs, startups, small business and Fortune 500s. And yes, this real estate move also now includes a WeWork app for members to “tap into the entire community of creators & entrepreneurs. Discuss ideas, find or list opportunities.” Neumann has taken to calling WeWork a “platform” powered by technology: “Our members are running their entire experience with WeWork through the app.”

That platform may have mutual benefits. By being early to market, scaling fast and tapping the billions in capital needed for rapid expansion, WeWork is gathering reams of data and insights on how we work, collaborate, create – and increasingly live. And that, in a sleekly designed nutshell, may be why this experiment is worth its $20 billion valuation and more.

This is the fourth in our How We Work Series, launched with stories on the San Francisco Runway incubator, the Galvanize all-in-one tech campus, incubator, and corporate innovation hub, and the foreign hub, swissnex. Sketches by Andreanna Woodhams, class of 2017, University of San Francisco. Stories and interviews by Jonathan Littman.