What’s an entrepreneurial mindset? And how can you can you cultivate one? Six months into the pandemic it’s clearer than ever – our professional survival depends on activating our entrepreneurial instincts. Where will we find the spirit and backbone to innovate? It just so happens that Susanna Camp and I have been hard at work on that task, developing a model to help you discover and trust your core identity, and embrace transformation as you tackle obstacles and opportunities.

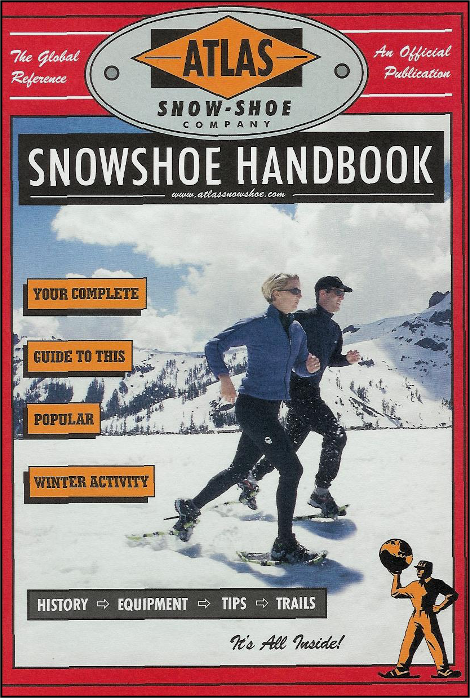

Pre-pandemic, two years ago, we hit the road and interviewed hundreds of men and women to find ten who perfectly encapsulate the essential entrepreneurial archetypes. They hail from Helsinki, South Africa, Estonia, and yes, California and the American Midwest. Each brings a highly particular slant to finding and making the most of life’s curveballs and opportunities. Welcome to our upcoming book, The Entrepreneur’s Faces, set for publication this September. Each week we’ll feature a preview of the opening chapter of one of our characters’ journeys here on our innovation hub, SmartUp.life. We know you’ll be inspired by their true stories, but we also believe it’s a fresh way of thinking about yourself and your team. These remarkable ten individuals each reflect an emblematic type. They are Makers, Athletes, Conductors, Accidentals – people who master challenges with a unique approach, and echo the models and behaviors of renowned innovators and entrepreneurs. They are all extraordinarily different, proving that ambition and accomplishment is anything but a one-size-fits-all proposition. They’re Faces, archetypes, and we know you’ll be drawn to find yourself in a few of them. This week you’ll meet Perry Klebahn, the Maker. We invite you to join him and the rest of our characters on this expedition.

[Below content is excerpted from The Entrepreneur’s Faces, © 2020 by Jonathan Littman and Susanna Camp. All rights reserved.]

Perry Klebahn’s Awakening

Perry Klebahn was one of the lucky ones, a young man who entered a university program designed to awaken budding product designers. Tall, lanky and athletic, with a direct demeanor, Perry had earned his bachelor’s in physics at Wesleyan, and enrolled in the mechanical engineering master’s program at Stanford. During the winter of his second year of graduate school Perry became intrigued by Design Garage, otherwise known as 116C. Less about theory and more about doing, the class was inspired by David Kelley, the charismatic founder of IDEO, the celebrated Palo Alto innovation and design firm with a golden touch – key to the success of dozens of hot tech products. Kelley was famous for his firm’s early, pivotal work for premier Silicon Valley companies, not the least of them Apple.

Candidates for Design Garage would meet during the fall with one of Kelley’s influential early IDEO staffers, Dennis Boyle, and explore potential ideas for new projects, only after this stage becoming eligible to apply. The students accepted into the course would spend the spring under the thrice weekly tutelage of Boyle, along with regular long weekly reviews with Kelley. The year was 1990, and it’s hard to understate just how radical this approach was for those pre-Internet days. No one talked about innovation. Design thinking was not yet on the map. Stanford’s celebrated and soon to be globally imitated d.school – integrating business, law, medicine, the social sciences and humanities into more traditional engineering and product design – would not be founded for more than 14 years.

That winter Perry drove up to Lake Tahoe, the Bay Area’s winter playground. He was the odd man out. Pained by an old ankle injury, he couldn’t join his buddies skiing or snowboarding. By chance, he found some snowshoes in the cabin, and decided on a lark to give it a try. Much to his surprise, he discovered that they were fashioned out of wood. Out on the snow he felt unsteady and kept slipping.

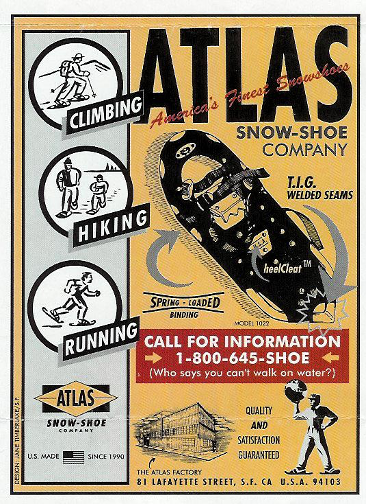

These pains sang to Perry like opportunities. As a mechanical engineer, he saw at a glance that snowshoes were still firmly stuck in the backwoods. The major improvements in light materials and flexible construction introduced in bicycles, cars, and airplanes during the latter part of the 20th century were strikingly absent from snowshoes. By now it was January. Perry had to come up with a project for Kelley’s Design Garage, and he thought: snowshoes. He wasn’t really sure how he’d redesign them, but he dove in. He knew how to make stuff: “It became these cycles of rapid-build on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday,” he said. Then he’d drive at the end of the week to the Sierras and test out his latest prototypes in the snow. “It was super fun,” he said. “It evolved from making this thing quickly lighter and faster.” Perry cobbled together aluminum tubing with a range of solid decking surfaces. Realizing that traction was essential to a superior on-snow experience, he began experimenting with bindings and a heel cleat.

Perry, as we’ll soon see, was not a typical student. He had a knack for making stuff, a burning natural tenacity, and the advantage of the structured, design- and market-focused techniques he’d gleaned in Stanford’s Design Garage. To his mind this wasn’t just a class project. Perry was making snowshoes, and he thought that if he put his mind to it, he could make one heck of a snowshoe. “I approached it as a startup from day one. I wanted to have a company, and this was going to be it.”

This enthusiasm was met with more than a little skepticism. Some fellow students criticized him for being too commercial, too focused on brand. But wasn’t that the point? To make something people wanted to buy? Some faculty members wondered if he was moving too fast, ignoring fundamental design principles. “It doesn’t look pretty. The design is not resolved,” one professor told Perry during a review. “I want you to do the curriculum.”

To which Perry had a ready retort: he had orders.

Next week: Allan Young, The Leader.