While interviewing members of Prince’s entourage following his death last month, what struck me, beyond their recollections of his indelible talent, was his voracious appetite for new ideas and his persistence at getting those around him to execute innovations on his behalf.

The best musicians have always pushed themselves and their collaborators over the line. Think Beethoven, Mozart — and, yes, Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, and David Bowie, to name just a few. But Prince was in a league of his own.

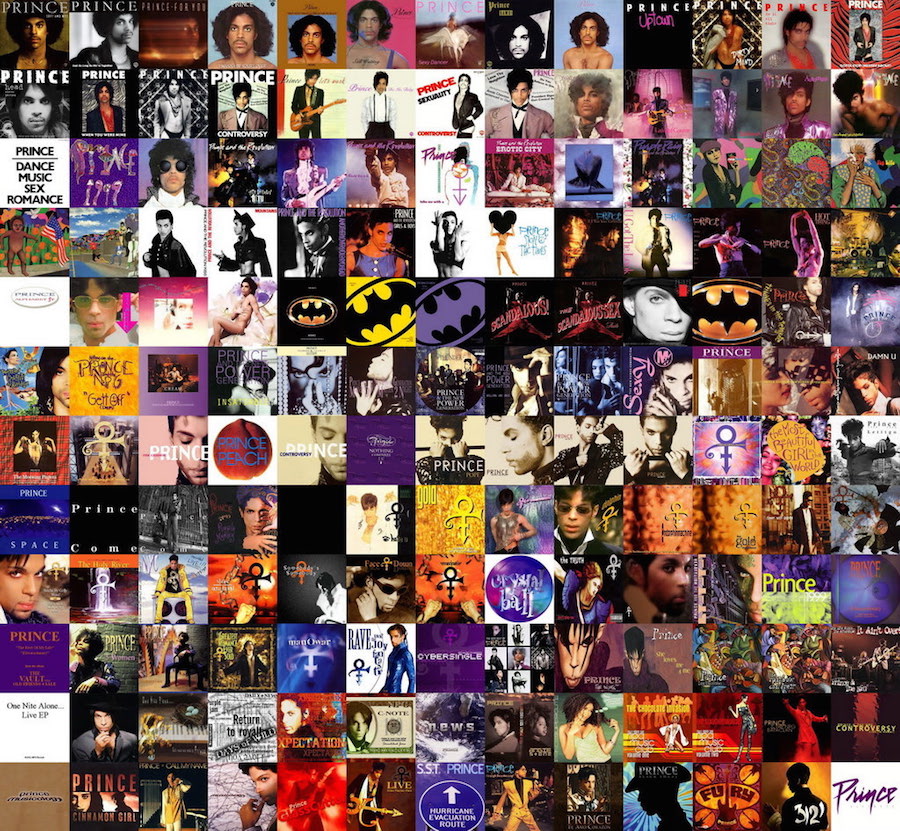

Known for his virtuoso guitar skills and musicianship — he would sometimes play all of the instruments on his albums — Prince also regularly tossed his artistic playbook to challenge himself and his audience. After the phenomenal success of his career-making 1984 album Purple Rain, when his fans and especially his record company would have welcomed nothing so much as Purple Rain II, Prince instead recorded Around the World in a Day, a dazzling collection of pop psychedelia that included “Raspberry Beret,” one his most beloved songs. As Michael Quercio of the band The Three O’Clock, which later released an album on Prince’s Paisley Park label, marveled to me after the performer’s death, “What superstar recording artist would follow up a mega success like Purple Rain with a psychedelic concept album?”

Prince was deeply influenced by Hendrix, who in the late 60s singlehandedly reinvented the vocabulary of the rock guitar through his innovative playing style (though a lefty, he played a right-handed Fender Stratocaster upside down and strung backwards) and wild experimentation with amplification and recording techniques. Hendrix treated the recording studio as a canvas and described sounds in a palette of colors and emotions. Collaboration was key. It was up to Eddie Kramer, Hendrix’s engineer, to help him achieve those novel sounds, and when Kramer succeeded —with a swirling guitar effect known as flanging — the guitarist rolled on the studio floor in delight.

Prince’s music was also heavily shaped by the Beatles, whose creative, technological, and business innovations transformed the industry: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, one of the first concept albums, would beget other landmark conceptual pieces like Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon and Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. Apple Records, the ill-fated, money-swallowing record label they founded in 1968, would nevertheless allow other artists — among them, Prince — to learn from their mistakes when they founded labels of their own.

The Beatles were well known for pushing George Martin, their producer, and Geoff Emerick, who engineered their recordings, to incorporate tape loops and other elements of avant-garde “musique concrète” into rock.

“I want the guitar to sound dirtier!” John Lennon hectored Emerick during the recording of “Revolution,” Lennon’s snarling B-side to the band’s 1968 smash “Hey, Jude.” As Emerick recalled in his memoir, Here, There and Everywhere, he was by then accustomed to Lennon’s inchoate but non-negotiable creative demands — he’d figured out how to put Lennon’s voice “on the moon” for the vocal on “I Am the Walrus.” For “Revolution,” Emerick hit upon the idea of sending Lennon’s guitar track straight into the studio’s mixing console, and cranking the controls to just below the point where the machine would overheat and explode. Emerick recalled thinking: If I was the studio manager and saw this going on, I would fire myself. But the experiment worked: Lennon’s “shredded” guitar licks, Emerick noted, would become the paragon, the gnarly guitar sound every grunge band in the world would aspire to two decades later.

Like Lennon, when Prince got an idea — no matter how fanciful — he was not at all interested in hearing about why it couldn’t be achieved. Patrick Whalen, one of Prince’s early production managers, told me that when he tried to inform the star that a certain lighting effect wasn’t possible, “He looked me in the eye and said, ‘So what you’re telling me is that in the two seconds it took you to say ‘no’, you left your body and went out and exhausted every possibility?’” Of course, after reconsidering, the production manager delivered to Prince the “impossible” effect.

John Mellencamp, a taskmaster on par with Prince during his prime, once ordered Kenny Aronoff, a right-handed drummer and one of rock’s most in-demand session players, to switch his drum kit around to force him to play left-handed during rehearsals for an album — anything, Mellencamp muttered to a bystander, to rid the atmosphere of innovation-killing complacency.

Hans Zimmer, the prolific multi-instrumentalist and composer who won an Academy Award for Best Original Music Score for his work on The Lion King, once told me that when he composes at the piano he literally sits on his hands until a musical idea is formed before actually playing it. Why? Because, Zimmer said, “the fingers, they just want to play the same old tired notes.”

What Zimmer, Mellencamp, Lennon, and Prince understood was that repeating your last performance isn’t the path to greatness. You need to innovate, and more often than not, that means taking risks and getting in people’s faces to achieve something extraordinary.

Fortunately, the risk-taking that defined Prince may soon become even clearer. Though the artist left no will, he recorded what’s been described as a vault of unreleased music thought to dwarf the prolific artist’s published recordings, and likely to reveal fresh layers of his unfettered experimentation. “When I first started out in the music industry, I was most concerned with freedom,” Prince said at his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2004. “Freedom to produce, freedom to play all the instruments on my records, freedom to say anything I wanted.”

President Obama recently gave tribute to his example. “‘A strong spirit transcends rules,’ Prince once said – and nobody’s spirit was stronger, bolder or more creative.”

For more on innovation in music and performance, check out Millennial Girl Meets Gen Z and So You Want to be Chosen?