From where I sit in Paris, an American living and working in France and the US throughout most of my professional life, I’d like to share my take on the EU’s new data protection and privacy requirements. Sure, this is about creating authentic, enforceable regulations for greater individual privacy – a controversial move in the US where dominant, mega platforms rule. But what many American techie critics miss is the upside: the potential to liberate latent market opportunities, especially for startups.

A quick tutorial: The EU’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) define new, easier-to-understand disclosures companies must make. They state upfront how they use consumers’ personal data, and clarify consumers’ rights to control, share (or not), transfer, and even delete their personal data. The new regulations also define penalties for non-compliance. That’s the essence of the legislation, intended to harmonize disparate data-privacy regimes across the EU, improve transparency and empower consumers.

Many American firms, and more than a few tech pundits, are now railing against the complexity of the GDPR. But legal frameworks rarely read like children’s stories. Consider environmental regulations limiting auto emissions and other carbon-based greenhouse gases (also of global concern and regulated by international bodies). Such laws are certainly voluminous and complex, but that doesn’t make them unnecessary or even especially difficult to implement.

Winners and losers

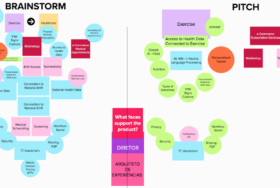

The cost and difficulty of compliance is proportional to a company’s size, history and geographic reach. Social media companies such as Facebook and other titans must now revise legacy systems, protocols and policies affecting how they conduct business across Europe. An upstart ready to emerge from the giant venture incubator Station F in Paris, on the other hand, can turn challenge into opportunity by adopting a “design for privacy” approach from the get-go.

The cost and difficulty of compliance is proportional to a company’s size, history and geographic reach. Social media companies such as Facebook and other titans must now revise legacy systems, protocols and policies affecting how they conduct business across Europe. An upstart ready to emerge from the giant venture incubator Station F in Paris, on the other hand, can turn challenge into opportunity by adopting a “design for privacy” approach from the get-go.

The behemoths clearly can afford to comply with the GDPR, and the implementation costs for newly incubated companies are modest. The biggest losers will be ventures in the US ready to expand internationally but now limited by expenses and potential penalties that could compromise their ability to scale.

For consumers, it’s simple. For anyone whose data is targeted (basically everybody using the internet), compliance means merely reconfiguring one’s settings and ticking a few boxes on or off. The GDPR involves minimal inconvenience and even offers a housekeeping opportunity as consumers get to 1) reaffirm their desire to receive companies’ content and services, and 2) select the data-privacy conditions under which they prefer to share their data with select services, their advertisers, and their partners.

Consumers have choices – and power

Part of the misunderstanding comes from faulty and sometimes disingenuous assertions about consumer behavior. Critics have concluded that consumers will simply hand over their data rights to the Facebooks of the world while denying such access to smaller firms, thereby reinforcing a competitive imbalance. But that’s not how consumers behave. Consumers make choices about their suppliers based on individual values, needs, desires and resources. Size matters, as does geography, and even category — whether social media, cars, toothbrushes, food or insurance.

From my perspective as someone who worked in venture capital and as a tech journalist, consumers don’t want their data shared willy-nilly with suppliers’ partners. If they’re going to uncheck that box for Facebook and Google, they’ll uncheck it for all other providers.

History teaches that empowering consumers triggers spurts of innovation. That’s how new markets emerge. Cars, banking, PCs, mobile phones and social media exemplify this natural phenomenon of opportunity incubation. Thanks in part to the GDPR, we may be entering a new era of advantage around the management and monetization of personal data.

Consumers already knew their personal data had value. Now, thanks to Europe, they have a way to control which advertisers, service providers, and social platforms can access, store and share that data. With that power comes a chance to negotiate an exchange in value, that is, rent their data to the highest bidder. Perhaps in return for discounts, for example.

Personal information managers (PIMs) have already sprung up to help consumers do just that. Applications that enable consumers to better manage and monetize their data are likely to follow. Aggregators, infrastructure management providers and application developers — including some promising startups and respected incumbents — are rushing to fulfill these needs and concerns.

Finally, the GDPR’s emphasis on simpler, more transparent language should help restore trust frayed by recent revelations of leakage, unauthorized transfers, negligence and other abuse. With data already well on its way to becoming an economic asset, addressing systemic risks like loss of trust can only help realize its full economic potential. Big data, as The Economist has written, is the fuel of the future, and we all would do well to think about it as a valuable resource.

The GDPR reminds us that regulations don’t always create bureaucratic friction. Nor do they necessarily destabilize competitive forces. Well-crafted international legislation can grease the gears of capitalism and spark innovation.

Startup Passion in Paris: Station F, Le Village, Ecole 42 … et plus