“What’s the proof?” demands the lanky man at the front of the room. “We’ve got the idea. But do you have a proof point? Did you sell anything? We saw that not only with you, but generally across the whole class. That failure to be specific about traction is shocking, right?”

It’s Day One of the Stanford Launchpad accelerator, a radically intense ten-week program designed to 10X ideas and founders, held in the university’s renowned d.school. This spring’s cohort is huddled tightly around a large whiteboard marked up with a ranking of their nascent startups. Roughly half will fail to find market fit or traction in the coming months. But for those who survive this entrepreneurial trial, the potential to scale is enormous. Launchpad is technically a college class – albeit an extraordinary, invitation-only one – not a full-scale incubator or accelerator. It’s condensed into just twenty two-hour sessions from April to June. But in the last nine years, Launchpad teams have raised an impressive half billion dollars in funding, and spawned dozens of thriving businesses.

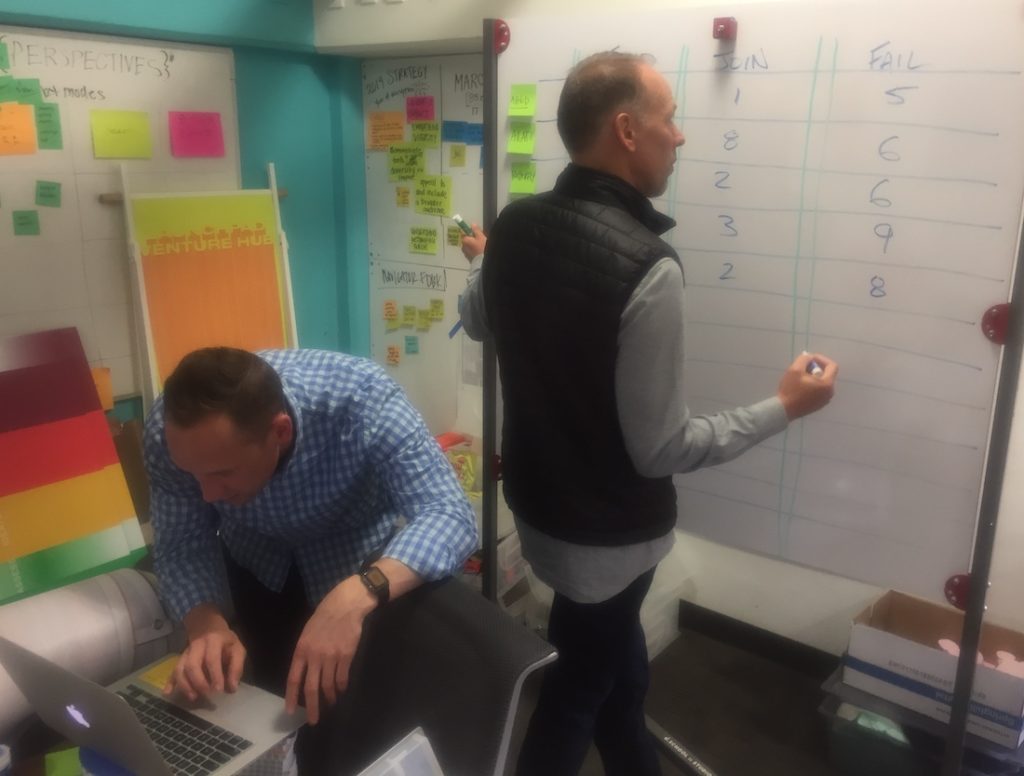

That’s Perry Klebahn leading the critique, co-founder of Launchpad, pulling no punches. By his side, Jeremy Utley, his long-time collaborator. The Stanford adjunct professors have just spent the last hour nearby in their post-it-festooned office studying a dozen videos from the fledgling teams. They’ve scrawled on the board the results of the student voting, each team having judged one another on these key criteria: Would you join it? Fund it? Or, conversely: do you think it will fail? Perry and Jeremy have appended their own assessments on post-its. And now the students are reviewing the outcome. The votes are stark, and brutal. A few select squads find that they are popular – receiving ample “join” and “fund” votes. Others have been punched in the gut: virtually nobody sees promise in their idea.

Next the teams regroup to reflect on the ratings and report back to the class. It’s a metacognitive exercise, not just about the scoring, but about the process of peer review. Such is the collaborative give-and-take nature of Launchpad. “This is actually a necessity that you get in each other’s business,” says Jeremy. “I see what you pitched. Now I have context. Many of you already know this to be true: Somebody else who has contact with your startup will help you more than you help yourself to make micro adjustments.”

The next assignment sounds deceptively simple: “What’s your product name?” asks Perry. “What’s the pain you’re addressing, and what’s the one function your product or service performs for that customer?”

Ten minutes later, the teams return to the whiteboard to post their completed worksheets. Product ideas range from entertainment to health to transportation and sport. Two target art – one team wants to build a model whereby artists will receive a share of future resales of their work, another seeks to enhance existing artwork through Augmented Reality. A few teams dive into music, fashion, creative writing. One all-female team has set out to create a superior tampon, while another strives to help women who experience pain during sex. A diverse team with medical and radiology expertise aim to label medical images. Another squad hopes to drastically reduce the cost of converting vans. Two guys have come up with an idea to help coaches win games through quizzing their athletes on plays.

Narrowing the Funnel

All too many struggle with the assignment. Most want to create something sweeping and expansive. “We tend to think whenever we’re defining opportunities, to define them as broadly as possible,” says Jeremy. But the problem is, they’re not actionable if defined too generally. “What makes for a spectacular prototype is focus. It’s no surprise, focus really matters.”

Specificity, he reveals, helps you learn quickly, whether you’re wrong – or right. And the key is to learn as fast as possible. He then launches into the example of the sports startup. “So let’s talk about specificity here. We’ve learned what kinds of teams matter. You focus on two sports [football and basketball]. It’s focused and narrow. So, it’s more believable. You can deliver that quiz. I’d push for you to think about which coaches are particularly feeing that fear or that pain, where the loss is unbearable. Maybe there’s a way to narrow that funnel a bit. Where are the coaches who are basically one dropped pass away from losing their job?”

Perry then jumps in, to critique the teams that got the most “apathy” votes on the video assignment. The first, an online service to give feedback on writing. An interesting idea, but … what kind of writing? School papers? Articles? Novels? His next target is a similarly opaque fashion platform designed to help young students and professionals look sharp on budget. “Students and young professionals are beyond enormously broad,” said Perry. He pauses and turns to the whole class: “You ended up with apathy because you stayed with vagueness, and vagueness is very difficult to figure out what to do as co-CEOs. They don’t even know what action to take.”

Back to the sports quizzing team. “Whereas here, I know what they need to build: quizzes that help this coach not get fired because somebody on this team doesn’t remember a play.” Perry shakes his head. “Vagueness is not your friend. It doesn’t help you at all.”

Day One of Launchpad is nearly over. The assignment due in 46 hours is to iterate with a reduced feature set. “Get to the core of what the thing is. For most of the teams, that’s going to be eliminating features, eliminating parts of the value proposition. Really hone in on the key value that you’re creating,” says Perry. The assignment also requires testing the refined product offering with six users. “We’re not building an entire platform in the next two days. We’re trying to get a singular feature you think is the crux of the interaction and prove that it works.”

Perry points to a post-it on the board describing the key feature of one team’s product idea. “This post-it is likely to change many, many, many times. Make sure you’re really passionate about this pain. We see over and over again that the entrepreneurs who are successful are in love with the problem, because the solution is going to change.”

And then the man whose first startup was a revolutionary snowshoe that launched an industry, leaves them with a metaphor: “You’re climbing a mountain, and then it’s a white-out. All you can do is take the next step. That’s where you are right now, because you’re not sure where the mountaintop is. If you take small steps,” he says, “you’ll get the most information.” And perhaps, by week ten of this intensive accelerator, they’ll find that often elusive market fit, gain traction, get funding, and yes, launch.