The Outsider: Silicon Valley’s most storied archetype. The brash entrepreneur with the chutzpah to reinvent a product or an industry. Hitch a ride on the journey of a young man who might be you or me. Daniel Lewis began on this path in his early twenties. He’d been an athlete. He’d worked at a think tank in the nation’s capital and wanted something more. His transformation did not happen all at once. He began studying law at Stanford, the sort of intensive discipline that normally precludes extracurricular pursuits. Daniel was curious and began asking probing questions of computer science professors and law librarians. This was no class project. But an unlikely quest to take on the industry, to overhaul how lawyers research judges and case law. He had the Outsider’s advantage. No attachment to the legacy of how things were always done. Here’s this week’s excerpt from our new book The Entrepreneur’s Faces. We hope it gives you a window on how you too might find the inspiration to take action on something just waiting to be innovated.

[Below content is excerpted from The Entrepreneur’s Faces, © 2020 by Jonathan Littman and Susanna Camp. All rights reserved.]

Daniel Lewis’s Awakening

Daniel Lewis’s parents were lawyers and the odds were high that he too would one day practice law. He’d worked one summer at his father’s boutique law firm before heading off to earn a degree in international studies at Johns Hopkins, and then quickly landed a plum job at a think tank in the nation’s capital. Daniel wanted to make a difference in energy and climate policy, and felt he was in the right place, working with the right people. But after a couple of years he began to question the reach of his individual impact. “It’s a very big ecosystem, there’s a lot of ways that policy gets made and shaped,” he recounted. “So it was becoming hard to figure out how I was putting points on the board.”

Daniel was competitive, a college baseball player, a pitcher no less, a young man who thought in terms of tangible accomplishments, measuring success in a pitch, strikeout, or win. Tall, with tousled hair, a square jaw and a dimpled chin, Daniel had classic athletic good looks. He applied to Stanford Law School, was accepted, and began class in the fall of 2009. He figured he’d end up a litigator like his father, or maybe since Stanford was smack in the middle of Silicon Valley, work in the emerging field of clean tech. But he also had a playful, creative streak. Within his first few weeks on the campus he toyed with creating a consumer product to help people select wines, even making some calls and talking to experts in the wine business.

The momentum stuck. During his second year he found a serious problem to tackle. It struck Daniel that the Stanford Law library’s digital tools seemed nearly identical to what he’d seen at his dad’s firm ten years before. Here in Silicon Valley, why were they stuck in this time warp, he wondered? All this great technology on the Internet, but why not in legal research? It was a problem he knew firsthand from researching case law for class. “The pain of it was that you could spend hours, and have very little confidence that you got the right answer, that you’d looked at everything that needed to be looked at.” Out in the real world, he knew, this could mean the difference between winning and losing a case. Daniel had a vision for something radically different, a “new kind of research that would be more visual, more data-driven.”

This had nothing, and perhaps everything, to do with attending law school. He saw his idea as a hobby, like the wine app that never went anywhere, or even the softball team he’d started at the think tank. Daniel liked to be busy, exploring new ideas, and he figured that at Stanford University, of all places, he might be able to get some answers.

He scoured Stanford’s computer science course listings, picked out some professors, and began randomly showing up at office hours. The professors were surprised. Daniel wasn’t enrolled in their classes. He was truly an outsider. He knew nothing about computer science. But still, after a little initial confusion about what he was doing there, the professors offered help. “I would show up, talk with them, and they would send me a couple of research papers relat- ed to searching legal cases or doing natural language processing.” Soon, Daniel was emailing post docs and IBM researchers all over the world, setting up phone calls “to learn what they were doing, and whether they’d carried their work forward at all.” All while studying law.

Next, he explored what was happening on the customer end. “I’d call the main line of a law firm, and ask to talk to the librarian,” he said. He’d probe how they felt about the tools they used. Did they hate them or love them? Wish there was a better technology? He told his subjects that he was a Stanford Law student doing research (which, strangely enough, was true). “I was getting a sense for whether there was any interest. Was I the only one feeling this pain?”

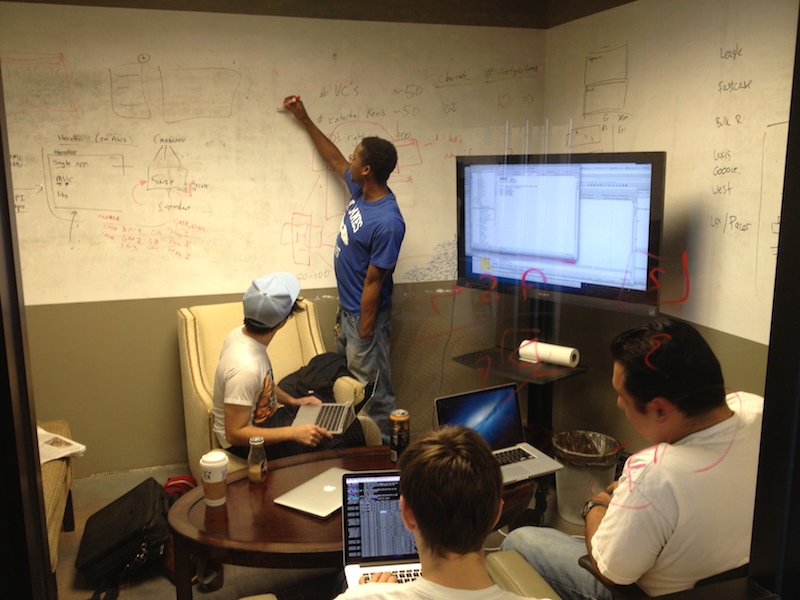

The beginner was quickly zeroing in on the opportunity, and uncovering the obstacles to innovation. There was a reason there had been a lack of technological advances in legal research. LexisNexis and Westlaw had successfully carved out an effective duopoly, a reality that Daniel saw in how the law firms he was interviewing felt about the company’s products, and their high pricing for the over one million lawyers in the US. “So that was new to me, I was learning the context of why these tools hadn’t changed much, and what the businesses that ran them looked like.” The summer before his final year of law school, Daniel teamed up with a friend studying at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “We started thinking about putting this down on paper. Okay, there’s some interesting technology out there, there’s a customer pain. But is there actually a valid product that you could build? What does the revenue model look like?”

Daniel had no business asking such big, fundamental questions, but the beautiful thing was that he simply didn’t know any better. The Outsider was starting to sense that this was becoming more than a hobby.

Next week: Karoli Hindriks, The Guardian